E G R O P O N T E

E G R O P O N T E

Let's dismiss that excuse once and for all, especially for thought leaders inside governments and NGOs, who must look beyond their individual terms in office and, in some cases, beyond their individual lifetimes. The same is true for anyone who wants to change the future economic well-being of his or her country, region, or the world at large.

Flatland

Young people, I happen to believe, are the world's most precious natural

resource. They may also be the most practical means of effecting long-term

change: Making even small opportunities for children today will make the

world a much better place tomorrow. Frankly, I have almost given up on

adults, who seem generally to have screwed things up despite the good work

being done in many parts of the globe. So I am increasingly inclined to

seek out ways for the 6- to 12-year-olds of our planet to learn how to

learn, globally as well as locally.

Education, however, is the formal jurisdiction of national, state, and local bureaucracies. And trying to bring about change through various ministries, departments, or boards of education tends to be a highly politicized and, at best, slow-moving process. Some ex officio move is needed, something outside the official fabric of school that can do for learning what the Internet has done for communicating.

Fortunately, there is a small, very basic step we can take today that will have a huge, lasting effect on tomorrow: Price local telephone calls at a flat rate. Though most people in the United States already enjoy flat rates, the same is not true, alas, in most of Europe or the developing world. Flat rates for local calls are universally employed in only 13 percent of the countries around the globe.

Sure, nothing is ever simple, but this one is real close. Unfettered access to the Net is key to the future of education. And learning, whether it's face-to-face or at great distance, takes time. Yet metered, by-the-minute pricing fosters short-term thinking in the most elementary sense. Instead of encouraging children to explore, parents nervously watch the clock as soon as their kids log on. The incentive is to have your child spend less time learning, not more - something unimaginable with a book or a library. Ironically, the high cost associated with time spent on the Net is not from Internet access itself, which is generally flat rate, but from the local telephone bill.

Metered billing has come about from, among other things, the historical limitations of circuit-switched voice networks. Telecommunications in most of the world has traditionally been a public utility, owned and operated by the government; people therefore assumed civil servants were providing the least expensive and most beneficial service. The benefits of increased telecompetition, of course, have now become clear. And as the pendulum continues to swing toward privatization around the world, national phone companies must dress up for the party.

Yet in anticipation of being privatized, some telcos have raised local rates. And even in markets where new economic models have emerged with the growth of packet switching, some are arguing to price data on a per-packet basis. This is crazy - and exactly the wrong way to go for Internet users, who want and need low and fixed local rates. Mind you, I am not saying free or even unreasonably low. Fixed.

Note to telcos: Take into consideration the cost of metered billing that you will now save by offering fixed rates. And give discounts for a second line. A lot of children will be better off for it.

TV may have it right

Though there is not much good that can be said for the vast majority of

television programming, the pricing model may be right. A large chunk of

worldwide broadcasting is advertiser supported, which makes it free to the

user. Another piece is provided via monthly fee or yearly tax. And a third

piece is paid per view. As telcos see themselves getting more and more into

the content business, this makes far more sense for their future, too.

Some 15 years ago, I jokingly suggested that the cost of cellular telephone calls should be supported by advertising. To my great surprise, this jest seems to be fast approaching reality. For the price of a few TV-like commercial breaks, people can now make free calls - local or long distance, wireline or wireless - thanks to the Swedish company GratisTel; Seattle's Network 3H3 offers similar ad-supported service.

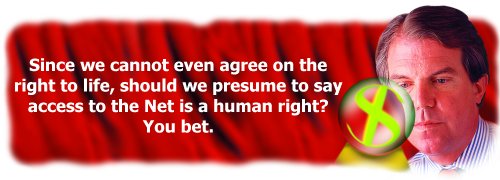

Should digital access be a fundamental human right?

"Extreme" though it may be, the idea of digital access as a human right has

been bantered about by some very staid organizations. Of course, even the

most widely accepted human rights are the subject of enormous, often

inconsistent cultural debate. Many people in the United States, for

example, both support the death penalty and oppose the right to have an

abortion. Now consider freedom of information. The Muslim world, for one,

is not so anxious to see universal access to the World Wide Web. Given the

amount of trash collecting out there, this is not so surprising. Since we

cannot even agree on the right to life, should we presume to say access to

the Net is a human right? You bet.

The only thing we know about the future is that it will be inhabited by our children. Its quality, in other words, is directly proportional to world education. While this can be improved by institutions and governments (see September's column, "One-Room Rural Schools"), the most rapid change will come from the personal resolve of millions of individual children. It will come from being passionate about the world, its people, and their knowledge. Unless we price access to the Net far more fairly than we do today, the dream will not become reality.

Get with it, telcos: Get rid of those meters. Time is running out.

Next: Beyond Digital

[Back to the Index of WIRED Articles | Back to Nicholas Negroponte's Home Page | Back to the Media Lab Home Page]

[Previous | Next]

[Copyright 1998, WIRED Ventures Ltd. All Rights Reserved. Issue 6.11, November 1998.]