|

Related Work

- Two-wavelength laser interferometry using superheterodyne R. Dandliker et al. Optics Letters 1988

- Femtophotography A. Velten et al. ACM Transactions on Graphics, 2013.

- Phasor Imaging M. Gupta et al. ACM Transactions on Graphics, 2015.

- Polarized 3D A. Kadambi et al. ICCV 2015

- Cubic meter volume optical coherence tomography Z. Wang et al. Optica 2016

- Superheterodyne interferometry using 1550-nm lasers F. Li et al. Applied Optics 2017

Bibtex

@article{Kadambioccluded2016,

author = {Kadambi, Achuta and Raskar, Ramesh},

title = {Rethinking Machine Vision Time of Flight with GHz Heterodyning, IEEE Access 2017},

journal = {IEEE Access},

year = {2017}

}

Contact

Achuta KadambiMIT Media Lab

achoo@mit.edu

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is this project about?

This is a form of LIDAR technology that studies how to bridge the gap between pathlength ranging systems that are optically incoherent (e.g. ToF cameras in vision and graphics)

with those that are optically coherent (e.g. OCT). What's interesting about the proposed method is that: (a) coherent methods typically require a matching of a reference and sample optical path;

while (b) electronic systems are limited to just a few 100's of MHz. In this project, we use a stack of carefully chosen filtering elements in order to demonstrate micron range precision with robustness to vibrations.

Why is micron-resolution important for LIDAR and time of flight systems?

Micron-resolution LIDAR is something we see as a sweet spot. It is not so precise as to be a laboratory technique (that can be influenced by air turbulence). On the other hand, the extra

precision wrt. commodity LIDAR systems (which operate at cm or mm resolution) enables new applications. For example, subsurface scattering in materials can be teased out using the micron-scale

pathlength changes. For 3D fabrication the resulting 3D scans would appear nearly photorealistic. Finally, for autonomous systems, the extra headroom in resolution could be used to compensate

for adverse conditions (e.g. at long ranges, where precision decreases).

What is new in the approach?

The novelty of our approach is to introduce a general formulation of having a cascaded stack of elements to perform ranging with. These filtering elements are analyzed in context of vibration cancellation, large frequencies, non-linearities in modulation, stability

in the beat note, and sampling rate of the detector. Stacking is also a path toward limiting the non-quadrature bias that is inherent to EO schemes, a topic we analyze theoretically. Finally, we demonstrate a prototype that achieves < 5 micron range precision and suggest a path toward wide-field implementation.

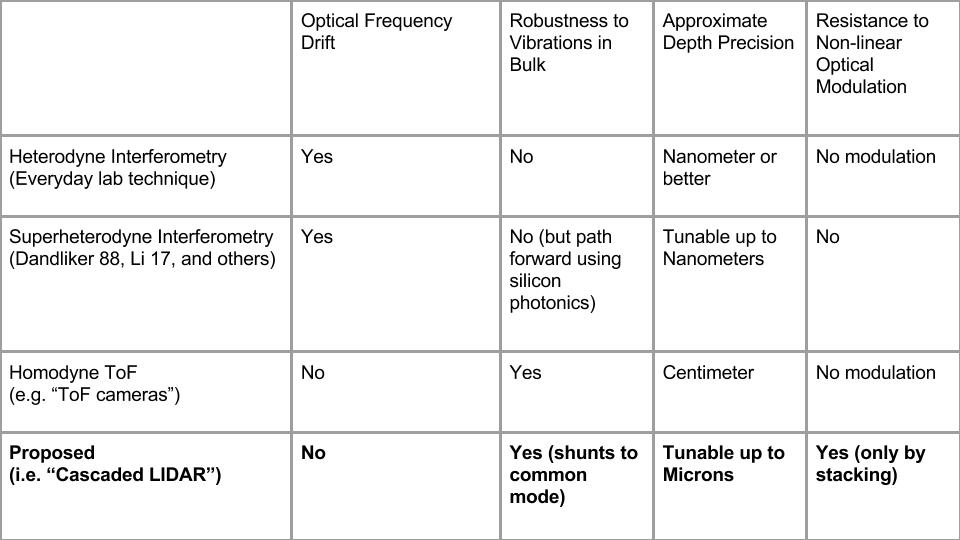

How does our technique compare with existing pathlength ranging systems?

A very similar and prevalent architecture to our technique are so-called "time of flight" cameras used in computer vision, computer graphics and robotics. The inclusion of beat notes in our formulation extends the frequency bandwidth

of time of flight cameras to the GHz regime. The resolution we obtain is close to what macroscopic OCT methods can achieve (e.g. Wang et al. 2016), but without the need for sampling of a coherence envelope. Our goals are similar

as compared to superheterodyne interferometry (Dandliker et al. 1988, and Li et al. 2017), but not reliant on optical frequency synchronization between multiple lasers. For a more complete picture, we direct the reader to these other papers in the field.

What are the drawbacks in our proposed approach?

The signal power of light is reduced as it passes through modulation elements. We construct a single-pixel prototype that will need to be later scaled to a wide-field setup. We find that non-linearities are avoided when using a multi-cascade. Using a multi-cascade can be expensive. Since

we are not using carrier frequency heterodyne (cf. superheterodyne), the maximum frequency bandwidth we achieve is far less than what superheterodyne interferometry can achieve superheterodyne interferometry (Dandliker et al. 1988, and Li et al. 2017).

What are some other applications of our work?

We have demonstrated pathlength control at a minimum of around 2-3 micrometers. This is about one tenth the width of a human hair. The long-term goal of obtaining such high pathlength accuracy is to potentially enable inversion of scattering or indirect reflections, by separating light paths. Properly executed, this could enable deeper studies on medical tisuse or higher-resolution forms of non-line-of-sight imaging (e.g. around corners).

Does the technique work in real-time?

At a single pixel, the results in the paper are collected in real time (faster than 30 Hz). However, we caution that a potential wide-field implementation requires scnaning at this time.